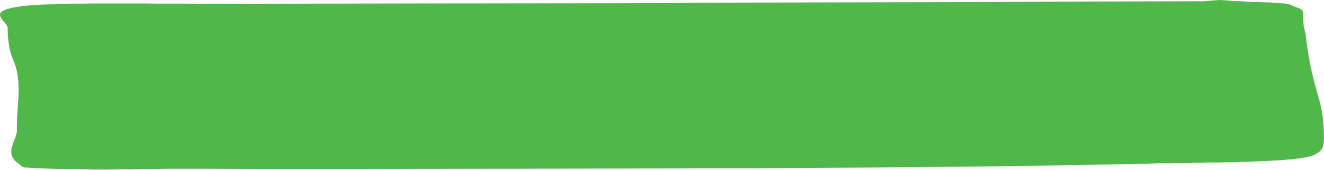

Paul Wood (left) and Trent Schatzmann with two of their three children. They want same-sex couples to have the same opportunity to adopt as other couples. Image credit: Rhett Wyman

As the proud adoptive parents of three siblings, Trent Schatzmann and Paul Wood believe there should not be any barriers for same-sex couples to adopt.

“Families come in all shapes and sizes and the way in which children are provided with a stable, loving home environment should not be determined by sexuality,” says Wood.

The couple from Lilyfield in Sydney, who have been together for 20 years and were married in Switzerland in 2012, knew they wanted to help children in need through permanent fostering or adoption. They approached Barnardos Australia because they knew the agency had advocated for the rights of same-sex couples to adopt.

The couple took in a brother and sister 10 years ago, then aged four and two, then their younger brother a few years later. Initially, they fostered the children, then adopted them. Like all adoptions in NSW, it’s an open arrangement where the children remain in contact with their birth family.

The couple say they have found fatherhood fulfilling, and have been embraced by their local community. They would encourage anyone thinking about having a family to consider fostering as a valuable way to do it.

Yet, in 2024, adoption is still not as straightforward for LGBTQ people as for heterosexual people because much of the work of government is outsourced to private agencies with a legal right to discriminate.

NSW changed the law in 2010 to allow same-sex couples to adopt children, but that law is inconsistently applied.

The NSW child protection system is heavily reliant on third-party providers, with more than 40 different fostering and adoption agencies, in what the Public Service Association has branded a “failed experiment”.

Each agency has its own policies: some only take couples not single people, upper age limits vary, and some openly say they do not place children with same-sex couples. The providers with religious affiliation are legally exempt from discrimination laws, despite being publicly funded.

Last year Australia was criticised in a United Nations report for allowing government-funded foster care and adoption agencies to reject prospective families based on sexuality, gender identity and faith.

In a recent case, Anglicare Sydney, an agency licensed for both fostering and adoption in the Greater Sydney region, refused to assess the aunt of an Aboriginal baby as a prospective long-term carer because she was in a same-sex relationship.

As first reported by The Guardian, the baby was instead placed with a non-Indigenous heterosexual couple and the Department of Communities and Justice recommended adoption.

NSW Minister for Families and Communities Kate Washington has asked for a review of this case and met with Anglicare Sydney to express her concern with its policy regarding same-sex foster carers.

LGBTQ advocacy group Equality Australia legal director Ghassan Kassisieh says: “The outdated prejudice of faith-based service providers must never take precedence of the lives and wellbeing of children.

“As a Christian man, I was offended.” – Dwone Jones

“People should be judged on their merits and not their sexuality, especially when a service provider is acting as an agent of the government.”

When Jay Lynch and Dwone Jones tried to adopt a child in 2012, they found their sexuality was an insurmountable hurdle.

The two men, who are celebrating 20 years together this month and are married, wanted to provide a home to a child in need rather than bringing a new life into the world.

The only positive response the couple received was from Barnardos Australia, but the agency did not cover Tamworth where they lived at the time.

Jones, who emigrated to Australia in part to escape the oppression he felt as a gay, black man in the United States, says he felt “surprised and hurt and angry”.

“We’re in the highest tax bracket and our government is taking our taxpayer dollars and putting it into these Christian organisations that, in my opinion, don’t reflect Christian values,” Jones says. “As a Christian man, I was offended.”

Lynch, an agnostic who grew up on Sydney’s northern beaches, was less surprised though also disappointed. He says if there had been options to adopt in Australia, he and Jones would have a family, but it’s now too late.

The couple also researched overseas adoption only to find many countries barred adoption to same-sex couples as well. They seriously considered fostering and attended a weekend course before realising it was rarely a pathway to adoption and deciding it was not for them.

“I realised that for me, I wanted to be a dad, I wanted to have a family, I didn’t want to be a ‘carer’ and they are two really different things,” Lynch says.

“I really admire people who are capable of providing that care that is so needed for a month, or three months or a year and then be comfortable with the child going back to their own family or to another environment, but it wasn’t something I could do.”

Schatzmann and Wood shared these misgivings, but took the risk. “We had originally wanted to take children with permanent orders, but when we took our [first] two children … it was under temporary orders,” Schatzmann says. “There were some stressful periods at the beginning, but it did become permanent, and then that did lead to adoption.”

However, the couple’s smooth run from being foster parents to legal adoption is unusual. Several dozen children are adopted by their carers every year, a fraction of the 15,000 children in care across NSW. Being in Sydney, they had more adoption providers to approach,

Besides the Department of Communities and Justice, there are 43 private agencies licensed to manage foster care in NSW, including 17 Aboriginal organisations specialising in First Nations children.

Just six of these agencies provide adoption services out of the child protection system, and two of them – Anglicare Sydney and Wesley Community Services – openly state on their website that they do not place children with same-sex couples.

The other four – Barnardos Australia, Life Without Barriers, Key Assets and Family Spirit – say they do not discriminate, but three of these don’t cover the whole state. Greater Sydney is well represented, but in some parts of NSW, there are only one or two adoption agencies in operation.

Anglicare Sydney and Family Spirit are the only two agencies that also provide voluntary local adoption services, where the birth parents voluntarily give up a child and the agency introduces them to prospective adoptive parents.

The NSW government is working on large-scale reform of the child protection system overall, including the arrangements for adoption, a process it says will take time.

A department spokesperson says it supports “all eligible families who want to adopt or foster children in NSW, including members of the LGBTIQ communities”.

Wesley Mission chief executive Reverend Stu Cameron says the agency tries to ensure children have positive, nurturing relationships with their biological mother and father and, when that is not possible, to provide them with carers who are similar to their birth parents.

An Anglicare Sydney spokesperson says the agency “serves in accordance with the doctrines of the Anglican Diocese of Sydney, which believes the best interests of a child are best served by giving access to both mothering and fathering, wherever possible”.

A spokesperson for Key Assets, which covers Sydney, the Central Coast and Hunter New England, says the agency supports adoption by members of the LGBTQ community when it is in the best interests of the child or young person.

Life Without Borders, which operates statewide, says it has been open to LGBTQ foster carers since 2001, but has only been licensed for adoption services since April 2023.

Barnardos Australia, which covers the Sydney-Wollongong-Newcastle region and out to Orange in the Central West, pioneered adoption to same-sex couples in 1985 by facilitating LGBTQ people to adopt as individuals.

Family Spirit is affiliated with the Catholic Church, but chief executive Sheree James says it operates at arm’s length from the church and assesses LGBTQ couples on an equal basis with other applicants.

The agency, which was established five years ago, operates its adoption services from out-of-home care in the Nepean Blue Mountains and Southwestern Sydney areas, but its small voluntary local adoption program is statewide.

James says about half of its applicants are LGBTQ. For voluntary local adoptions, it is up to the birth parent to choose the adoptive parents, and most are open to LGBTQ couples.

“I remember one woman saying she would love to have her baby adopted by two dads because then she would always be her mum,” James says.

This article first appeared in The Age here.